Prospectors joining the dot-com gold rush in the ’90s were mainly coming from large organizations seeking to capture some of the new wealth. But along with the promises of stock options and casual dress came another bonus — no bureaucracy. No meetings! No Microsoft Exchange! And no more onerous management systems.

Prospectors joining the dot-com gold rush in the ’90s were mainly coming from large organizations seeking to capture some of the new wealth. But along with the promises of stock options and casual dress came another bonus — no bureaucracy. No meetings! No Microsoft Exchange! And no more onerous management systems.

Disciplined startups recognized that management systems were important — for setting and hitting milestones, and for giving employees adequate frameworks to perform and feel good about themselves and their company. But more often there was extreme swinging of the pendulum that led to free-wheeling, hair-on-fire mismanagement, wildly missed targets . . . and lots of disgruntled campers.

Driven by the mantra of ‘first to market wins,’ dot-com startups were hiring way too fast, pushing employees way too hard (I remember one of our VCs saying he expected all employees to keep a sleeping bag at the office), and eschewing management systems entirely. In the end, a lot of folks went back to their big companies, happy for a return to structure, sanity, and their 401k . . . even with a pay cut.

The fact is, every organization needs a management system. It just needs to be appropriate for the company’s stage.

Much has been written about motivating employees. The admirable folks at web-app developer 37 Signals (makers of Basecamp and other popular utilities) espouse a four-day week and flexible hours, and for the most part, I ascribe to their philosophy. But I also have seen lots of companies provide increasing perqs to increasingly dissatisfied lots of employees.

What it gets down to is that providing the right amount of structure, goal-setting, and feedback — and communicating clearly — does more for esteem and spirit than all the free food and Friday afternoon keggers ever will.

After a six-month stint consulting for a startup to help it transition from a service to a product business, I joined the company full time as COO. It had about 20 employees. The CEO had good transparency — employees got monthly updates on progress and direction — but individuals had tasks, rather than goals, and no way of seeing how their roles fit into the bigger picture.

This is one of the key tenets of management: people want to know how their contribution fits in — how their efforts (along with their counterparts’) ‘roll up’ in support of the company’s overarching goal.

One of my charges was to institute a planning and management system. And it’s honestly one of the most satisfying aspects of management — especially when you see people responding . . . when they come by at the end of the day to tell you ‘I really appreciate what you’re doing here,’ or ‘we really needed this.’

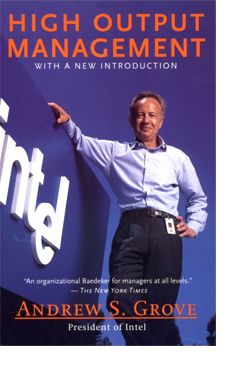

Startups’ management systems (and culture) are usually brought by the founders from their antecedents. Most of my management experience came from a manufacturing startup. My co-founder came from chip-leader Intel Corp. — along with a fairly high percentage of our initial hires — we essentially followed Intel’s management disciplines, policies, and procedures. In hindsight, it was one of the smart things we did. Intel was an extremely well run company. (I subsequently became a huge fanboy of then-CEO Andy Grove and his management books.)

I adopted Intel’s Quarterly Objectives and Key Results methodology, and have used it (with a few of my own variations) ever since.

To be sure, shipping a manufactured product requires a different discipline than the ‘just get it out there and revise it later’ strategy of web apps. But certain management principles are universal, and over the course of working both in hardware and software companies, I came to understand which ones they were.

One of the principles that always took a while to convince people of was the work-week calendar. Lots of them are available, but in particular, many manufacturing companies split the year up into four 13-week periods . . . usually with ‘4-4-5‘ months. (Mainly to ensure a ‘linear shipping’ schedule, making it easier to hit quarterly shipment targets and to compare quarter-to-quarter performance.) But it’s something I found to work well in hardware, software, and Internet businesses.

Why? Because over time — it usually takes three quarters or so — the numbered weeks start to stick, and people in the company realize that it’s a lot easier to reckon you have 11 weeks till year end (we’re in Week 41 right now) than calculating the number of days between October 8 and December 31. More importantly, employees and managers get into a recurring 13-week rhythm, which has certain psychological advantages.

And why is it so important to think in terms of quarterly performance? Whether you’ve just got plans to make money, hit revenue and profit targets, and grow — or serious ambitions to become a public company (IPOs will return someday!) — ‘making the numbers’ each quarter is a discipline that should begin early.

Next post: The Basics of the Quarterly Objectives process.